Game Engine Explorations: Name, Base Design and Logging

In this post, I will not get to the point where I can show a graphical window. Before jumping to the graphical world, I will write about the basic design for the engine. This will only cover the entry point and the base Application class. Additionally, I will give an example of a component by implementing a logging service.

Choosing a name for the engine

I decided to call this engine tamarindo, after the fruit and a beach in my home country. I will use that name for the engine’s namespace. For macros, I will use the TM_ prefix.

On to the basic design

The project creates a solution with two projects: a static library and an executable. I will refer to these projects as the engine layer and the application layer. The engine layer has all the generic and required core to create a graphical application. The application layer has the specific code for the application. It extends over the engine layer to describe an application. This diagram explains it better:

+------------+

|Application | +-----------+

|(base class)| |entry point|

+-----^------+ +-----^-----+

| |

engine_lib.lib | | Engine Layer

----------------------+-------------------+---------------------------

game_app.exe | | Application Layer

| |

+-------+-------+ +------+------+

|GameApplication+----+main function|

|(game logic) | +-------------+

+---------------+

The engine layer is independent and can be reused in other application projects. This modular design eases development, iterations and testing.

As the diagram showed, the main function yields the execution to the engine layer entry point:

// game_app/main.cpp

#include "engine_lib/core/entry_point.h"

int main(int argc, char* argv[])

{

return tamarindo::main(argc, argv);

}

The tamarindo::main function is responsible of creating, initializing and starting the application:

// engine_lib/core/entry_point.h

namespace tamarindo

{

int main(int argc, char* argv[])

{

std::unique_ptr<tamarindo::Application> app = CreateApplication();

if (!app->initialize()) {

std::cerr << "Could not initialize application\n";

return -1;

}

std::cerr << "Starting application...\n";

app->run();

app->terminate();

return 0;

}

} // namespace tamarindo

The run routine will take control of the execution and start the application’s main loop. This may change in the future if I ever get to have multithreaded services.

The Application class is in control of the graphical application. The application layer must create a derived class and override the abstract functions. The Application class call these functions to execute the logic code. In this first iteration, the class looks like this:

// engine_lib/core/application.h

namespace tamarindo

{

class Application

{

public:

virtual ~Application() = default;

bool initialize();

void run();

void terminate();

private:

virtual bool doInitialize() = 0;

virtual void doTerminate() = 0;

};

} // namespace tamarindo

This class shows some patterns that I will use in this project. The base class implements the public API functions. These functions call the private virtual functions. The application layer is only required to implement them. These functions follow the naming convention do + base class function name.

Another pattern that shows up here is the initialize/terminate functions. It is quite common in C++ to rely on the RAII principle to design classes. But, I want to be explicit with resources initialization and termination. This pattern will also be present in the design of internal components.

Finally, the application layer is also required to implement this function:

// engine_lib/core/application.h

extern std::unique_ptr<tamarindo::Application> CreateApplication();

As shown above, the entry point will use this function to create an instance of the application.

The first component: logging

Using <iostream> from the beginning is quick and easy but can become a headache to replace later on. That is why I will implement a logging service that I can change, iterate and improve.

For this service, I will use the spdlog library. This library is fast, it uses the fmt library, and it can be customized to output logs to files or console.

The first step is to clone the repository as a submodule. I will do it in the sources/engine_lib/external folder. This library can be used as a header-only library, or it can be compiled as a static library. For now, I will use it as header-only, so there is no need to create a premake file for it. To manage include folder paths, I will create the premake/dependencies.lua file. This file will declare a global hash map with paths relative to the root folder:

-- premake/dependencies.lua

-- Copyright (c) 2021 Emmanuel Arias

IncludeDir = {}

IncludeDir["spdlog"] = "sources/engine_lib/external/spdlog/include"

Then I can include this file in the main premake5.lua file to make it available to all premake files:

-- premake/premake5.lua

include "dependencies.lua"

And finally register the folder in the projects' premake files:

-- sources/engine_lib/premake5.lua

includedirs {

(ROOT .. PROJECT_ROOT .. "engine_lib"),

(ROOT .. "%{IncludeDir.spdlog}")

}

As I mentioned before, the Logger class is the first of the Application components. Here is the first definition of it:

// logging/logger.h

namespace tamarindo

{

class Logger

{

public:

void initialize();

void terminate();

// ...

// There will be only one logger instantiated

static Logger* getLogger();

private:

static void provideInstance(Logger* instance);

};

} // namespace tamarindo

Here is another pattern that needs some explanation. More often than not, global resources are not recommended to use. But, some APIs are designed to be unique and accessed by many components. One example of these APIs is the logging service. Passing a pointer around for logging does not sound like a good decision. Here I am borrowing from a chapter in Robert Nystrom’s “Game Programming Patterns” book. You can read it online here.

I defined the s_LoggerInstance pointer in an anonymous namespace in logger.cpp. This will give the variable internal linkage, i.e. it will only be accessible by the translation unit. For more information, refer to this link. The logging service instance will be accessible by a public getter in the Logger class.

// logging/logger.cpp

#include <iostream>

namespace

{

tamarindo::Logger* s_LoggerInstance = nullptr;

}

namespace tamarindo

{

void Logger::initialize() { provideInstance(this); }

Logger* Logger::getLogger()

{

// TODO: check if null

return s_LoggerInstance;

}

void Logger::provideInstance(Logger* instance)

{

// TODO: check if exists

if (s_LoggerInstance == nullptr) {

s_LoggerInstance = instance;

}

}

} // namespace tamarindo

For now spdlog initialization is quite simple. I will output to the console with some simple formatting:

// logging/logger.cpp

void Logger::initialize()

{

spdlog::set_pattern("[%T] %^[%l]%$ %n: %v");

m_SpdLogger = spdlog::stdout_color_mt("TM_CORE");

m_SpdLogger->set_level(spdlog::level::trace);

provideInstance(this);

}

void Logger::terminate() { m_SpdLogger.reset(); }

{```

The logging API functions are defined in the header, because they rely on templates:

```c++

// logging/logger.h

template <typename... Args>

void trace(fmt::format_string<Args...> fmt, Args &&...args)

{

m_SpdLogger->trace(fmt, std::forward<Args>(args)...);

}

and to make things easier, I defined macros:

// logging/logger.h

#define TM_LOG_TRACE(...) ::tamarindo::Logger::getLogger()->trace(__VA_ARGS__)

The API offer the logging levels trace, info, debug, warn and error.

To test things, I added some logs to the intialize and terminate functions:

bool Application::initialize()

{

// Initialize internal modules here

m_Logger.initialize();

TM_LOG_DEBUG("Initializing application");

return doInitialize();

}

void Application::run() { TM_LOG_DEBUG("Running application"); }

void Application::terminate()

{

TM_LOG_DEBUG("Terminating application");

doTerminate();

// Terminate internal modules here

m_Logger.terminate();

}

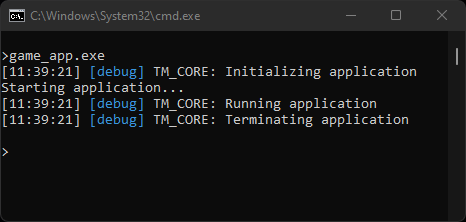

Executing the current application will give as output:

No graphics so far, but I promise it will come out soon. You can find this project on my Github, and the code from this post is in this commit.

In the next post, I will introduce GLFW and have the first window application running. Thanks a lot for reading :).